XYLOGRAPHY

Xylography is the French term for the process of making prints with woodcuts or wood engraving. It was also used to describe the process in Germany, and less so England, from the beginning of the nineteenth century. The process itself was invented in 800 BCE, when Chinese printers first turned woodblocks upside down, placed paper on top, and applied pressure to the back of the paper with brush, baren or another burnisher. In Europe, so-called block books were produced from the early fifteenth century, where the image and text were cut in reverse directly onto the flat plank for printing, a form that continued long after the invention of moveable type in Europe. The most important development for woodcut blocks was their combination with movable type in the German printing innovations from the 1460s.

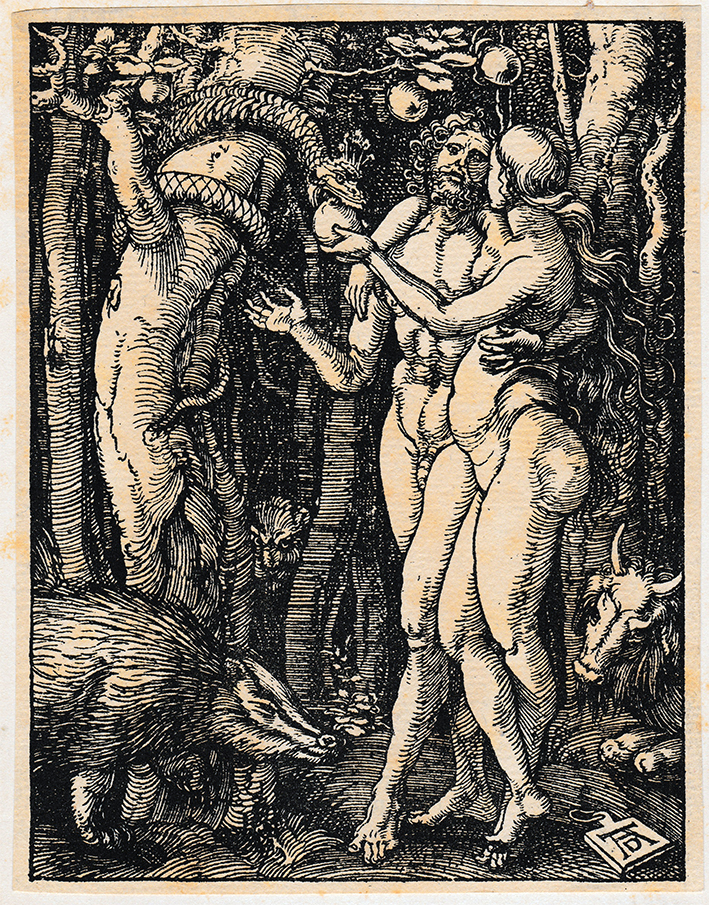

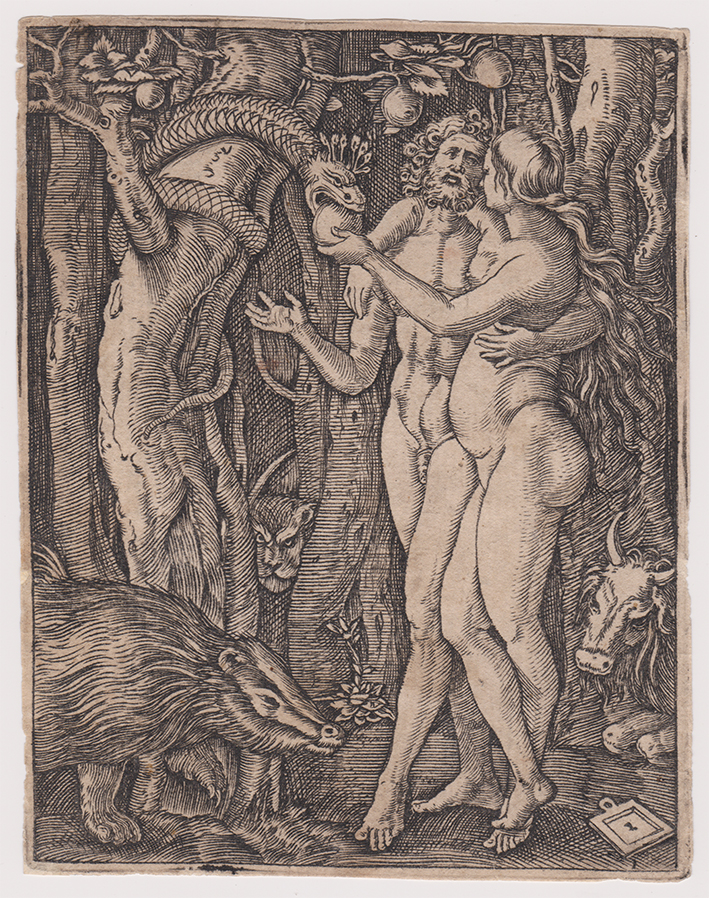

The lifetime of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is the usual measure of the first golden age of the woodblock. His towering presence is felt not only through the distribution of woodcuts from his own workshop but also through that of imitators and copyists of his work across Europe. Among them was the Italian Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1480–c. 1534), who made his copies as copper engravings. It is instructive to examine his technique in the copy of Adam and Eve from Dürer’s Small Passions (c. 1510) to see how he adapted his cutting style to the demands of the engraver’s craft.

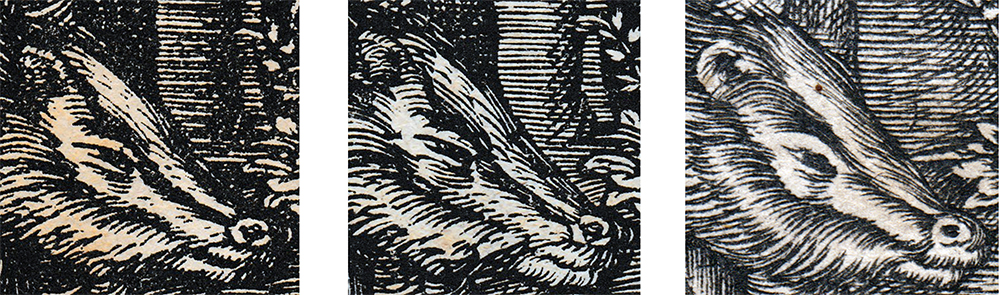

However, the most infamous copies of Dürer’s Small Passions are those of the mysterious Johann Mommard, who copied all thirty-six woodblocks of the series and printed an edition in 1587, about sixty years after Dürer’s death, and another in 1644. The awesome skill involved in this deception by Mommard is such that only a close comparative physical examination of many of the prints can separate the originals from the copies. This exhibition offers viewers the opportunity to examine three versions of The Entombment as it appears in Dürer’s Small Passions. One is from Dürer’s original block, printed in the 1600 Italian edition of the Small Passions; another is an exact copy printed by Mommard in 1587 from his own woodblock; and finally a lithographic facsimile from 1888 completes the three-way comparison. The point to be made in this exercise is that it would be impossible to pick the Dürer original from reproductions of the three. To show the degree of difficulty below are details of the above Fall of Man. The engraving by Raimondi on the right is obvious but the Durer left and Mommard centre are not so easy to differentiate.

Thomas Bewick (1753–1828) pioneered the second xylographic revolution with the development of engraving on the end-grain of the woodblock. Although lithography became a very popular nineteenth-century print medium in France, most of the nineteenth-century illustrations from the popular press in Australia, England and the USA made before about 1880 are wood engravings. When Bewick began his book illustrating, the maximum size of a prepared boxwood block was about 10 x 15cm, which was ample for the size of his engravings such as his New South Wales Wolf (1790). When demand increased for larger full-page images in illustrated papers such as the Illustrated London News, these small blocks had to be bonded together with various techniques, but most commonly a combination of tongue and groove and tension bolts. The seeming limitation of the small boxwood unit became an advantage as the engraved images became larger and publication deadlines tightened. The jointing process allowed the intensive labour in cutting the blocks to be divided across a team of engravers. This explains why occasionally a strange sheer or slippage, like a glitch on a digital image, appears when two different engravers’ work does not line up after the block is put together, not to mention the white lines that appear when the blocks begin to come apart. This only occurred after extended use, as editions over 400,000 from one block were possible. The blocks themselves were valuable commodities that could be recycled or sometimes recut for later use. For example, Sam Calvert’s wood engraved blocks of Ned and Dan Kelly published in Illustrated Sydney News in 1878 were reused five years later in a phrenologist’s publication in Melbourne to demonstrate the “animal propensities” of the two men.[1]

[1] Rev. Ralph Brown, A Delineation of the Character, Talents, Physiological Developments and Natural Adaptations of M---------------- (Melbourne: Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, 1883).

R. Woodrow Sept. 2019

Samuel Calvert (1828-1913) wood engraving 1878. The Bushranging Outrage in Victoria. (Kelly gang and murdered police) Illustrated Sydney News 1878. [note on show at Logan]

Thomas Bewick The New South Wales Wolf 1790 wood engraving 5.4 x 7.8 cm private col.

Sam Calvert “Animal Propensities”, wood engraving 1883 published in R. Brown A Delineation of Character… Melb. 1883 p 24. [not on show at Logan]

Copyright © All rights reserved

![Samuel Calvert (1828-1913) wood engraving 1878. The Bushranging Outrage in Victoria. (Kelly gang and murdered police) Illustrated Sydney News 1878. [note on show at Logan]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1567009542141-375R708ZLDSWO3JPPXX7/NedKelly-1WEB.jpg)

![Sam Calvert “Animal Propensities”, wood engraving 1883 published in R. Brown A Delineation of Character… Melb. 1883 p 24. [not on show at Logan]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1567009442348-9PO8P5EK12NY5FQKAJ13/NedKelly2WEB.jpg)